When we reflect on India’s 71 year-long independence in context with real estate, one thought overshadows all others – affordable housing. No nation can call itself truly self-sufficient until there is a roof over every head.

We can talk about increased transparency and efficiency, but this has true relevance only if it is not just the industry that benefits but also the common man.

Embodying this very basic but profound premise, the Modi Government’s election manifesto of providing Housing for all by 2022 definitely rang all the right bells.

Obviously, it boils down to unleashing a massive number of affordable homes, and the Government has certainly gone the extra mile to making that happen. Unfortunately, what we have seen so far is more marketing hype than genuinely affordable housing.

Many developers have climbed on the ‘affordable housing’ bandwagon, but actually the term ‘affordable’ is in most cases just being misused to ostensibly show alignment to the ‘Housing for All’ mission.

Of course, builders have been generously applying terms like ‘affordable’ and ‘luxurious’ to projects which were neither affordable nor luxurious long before the Modi Government took charge in 2014.

However, almost every second project today is being purveyed as ‘affordable’ and people can still not afford to buy homes there. There appears to be a big intelligence gap when it comes to the real definition of affordable housing.

What is affordable housing in India?

According to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, affordable housing is defined on the basis of property size, its price, and the buyer’s income.

For instance, for the economically weaker section (EWS), an affordable house must measure between 300 and 500 sq. ft. and be priced below Rs 5 lakh, incurring no more than Rs. 4,000-5,000 as monthly EMIs. The income ratio, in this case, should be of 2:3. These numbers change for lower income group (LIG) and the mid-income groups (MIG).

The central bank’s definition, on the other hand, is based on the loans given by banks to people for building homes or buying apartments. It recently tweaked the incentivised affordable housing loan limits from Rs 28 lakh to Rs 35 lakh in metros and from Rs 20 lakh to Rs 25 lakh in non-metros, provided the overall cost of the home doesn’t exceed Rs 45 lakh and Rs 30 lakh respectively. This move was aimed to give a fillip to low-cost housing for the EWS and LIG groups.

Thus, the definition changes according to the context. Some builders even use the term ‘affordable luxury’, whose validity is again very context and location-based.

How much of the upcoming supply qualifies?

As per ANAROCK data, as many as 22,120 new units were launched in the affordable category (< Rs 40 lakh) in Q2 2018 across the top 7 cities. Affordable housing units comprised a massive 46% of the total new supply in the same quarter.

If we break these numbers down further, then nearly 6,530 units were launched in the price bracket < Rs 20 lakh, and the remaining between Rs 20 lakh to Rs 40 lakh.

The supply in the affordable housing segment (< Rs 40 lakh) saw an increase of 100% in Q2 2018 as against the previous quarter. In fact, the overall supply in Q2 2018 was dominated by the affordable segment, with nearly 46% supply in this category which eventually boosted the overall supply growth.

However, around 2,37,000 units in the affordable segment (units priced less than Rs 40 lakh) were unsold as of Q2 2018 across the top 7 cities. This number pertains only to the unsold units of organized private developers, and does not include Government housing schemes. If those are included, the figures would go further northwards.

Here is a paradox. While there are ample options in the affordable category which can easily bridge the demand-supply gap, the numbers speak otherwise. Yes, more potential buyers are now eligible for bank loans – but due to rising NPAs (particularly in the real estate sector) banks are being extremely cautious in lending to both builders and buyers.

Affordable luxury

The terms ‘premium affordable’ or ‘affordable luxury’ are coined by developers to leverage the ‘affordable’ buzzword in the Indian real estate sector. Such projects may boil down to normal mid-range housing with some extra amenities thrown in.

A parallel that could be drawn is the air ticket category ‘premium economy’, which offers some extras but isn’t quite business or first class.

In a limited number of such projects, there is genuine added value for a slightly higher price. Others may be normal mid-range projects with a fancy name. However, by no stretch of imagination can one claim that the supply of ‘affordable luxury’ housing is in any way geared to help meet the Government’s ‘Housing for All by 2022’ target.

‘Honey, I shrunk the flat!’

Let’s face it – only compact housing is really affordable. Affordability in any category actually depends on the location, the builder’s brand value and property specifications, but size is obviously the primary criterion.

Most metros are seeing the emergence of the ‘small is beautiful’ trend. Compact homes have become the new mantra for affordability in pricey cities and locations.

If we consider that even the lower-income groups need to be able to live in our cities, this makes sense – and this supply can in many cases be aligned to the affordable housing category targeted by the Government.

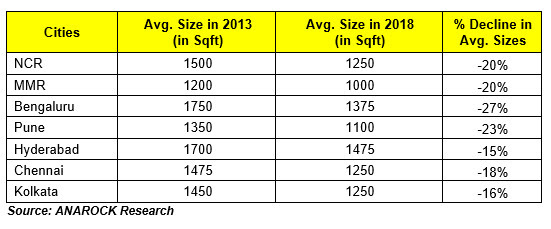

In fact, the average size of properties is shrinking in most cities to suit the ‘affordable budget’ of most buyers. If we consider the yearly trends, average unit sizes in Bengaluru shrunk from 1,478 sq. ft. in 2017 to nearly 1,334 sq. ft. in 2018.

Other cities followed suit with overall sizes of properties seeing a downward trend over the last three years. In fact, if we plot the ‘honey I shrunk the flat’ syndrome from 2013 onwards, it emerges that apartment sizes have reduced by anything between 15-27% in the top seven cities.

Again – a home for every Indian by 2022?

Obviously, the Government’s spate of policy reforms and schemes over the last few quarters has resulted in an increased new supply and also demand for affordable housing.

However, ‘housing for all’ does not necessarily mean ‘every Indian family owns a home’ – we are in any case nowhere near to such a target. This concept must evidently also include rental housing which those who cannot afford to buy can avail comfortably within their means.

If we look at it that way, we may be a lot closer to the Government’s target than it seems. If RERA spreads its wings as intended and has the expected nation-wide impact, a lot of inventory will hit the market over the next 2-3 years.

Attracting end-users aside, the next necessary step would be to entice investors who can buy and rent out this inventory back onto the market.

Boosting rental housing

This is quite a challenge, considering that the Indian real estate market currently favours end-users – and that too largely only for ready-to-move options – but is rather unattractive for investors.

What is required is that the GST rates for affordable housing be significantly reduced, or that affordable housing is exempted from GST altogether. GST has resulted in reduced buyers’ interest in new launches and under-construction projects.

With minimal customer advances, the liquidity crunch has stalled construction of several projects. Despite having all the approvals in place and the developers will to complete these projects, lack of funds is acting as the main barrier.

Besides the reduction of GST rates, the Government must intervene to allow bank funding to developers for land purchase. Allowing banks and HFCs to fund land purchase will help developers bring down their costs significantly, which in turn can be passed on to the buyers.

In the absence of a bank finance, developers resort to PE funding and other non-formal modes of funding to finance its land purchase which increases the cost of capital for them drastically.

Investors have historically sought to leverage the lower price points of under-construction properties and tend to focus on emerging growth areas – which are also affordable rental locations. On project completion, serious investors will put their holdings on the rental market until the desired price appreciation is achieved and selling the properties makes sense.

Since it will take at least 3-4 more years for serious price appreciation in viable emerging areas to manifest, we would have a sizeable rental market.

Boosting rental housing demand and absorption can go a long way in meeting the ‘Housing for All by 2022’ target that the Government should consider seriously.

Perhaps then, we could celebrate our independence day in 2022 with this dream fully realized. Hope spring eternal, as does human endeavour.