In India, caste matters and so does colour

Ginni Mahi through her music chooses to defy society’s preferred order. She has used her music to assert modernity’s most cherished notion—equality. That is her greatest victory.

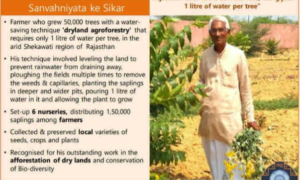

Performance by Ginni Mahi at Haridwar, Uttrakhand. Pic credit : @ginnimahi.singer

Ginni Mahi is 17. But, while there’s something of the bubbly teenager in her, she also exudes immense confidence in a manner that few teenagers, especially from a background like hers, do.

Especially, in the northern Indian state of Punjab where she lives.

Ginni, whose original name is Gurkanwal Bharti, is a Chamar, a leather-worker by caste – in India’s traditional caste system among the lowest castes and an ‘untouchable’.

For the past seventy years, the fact that untouchability as a practice exists even though it is banned by law has been one of India’s worst-kept secrets. This practice has manifested in several forms.

In a recent book, A Feast of Vultures, by investigative journalist Josy Joseph that documents India’s many corruption scandals, one of the most heart-rending stories is of a village in Bihar and its struggle for a road. In telling that story, Joseph also details in pitiful detail the plight of the lower castes of the village.

The lower caste settlement is on the fringes of the village, away from the caste Hindu settlements and definitely at a good distance away from places of worship. Most lower-caste families are landless and work as agricultural labourers at starvation wages.

Electricity and sanitation are non-existent. Those who do manage to extricate themselves from the cycle of poverty do so by migrating to cities and sometimes even masking their caste identities. Upper-caste Hindus are often reluctant to rent homes to the lower castes.

Given these steep obstacles, it is more than surprising to hear Ginni state her caste identity brazenly.

Over a year back, she released a song, Danger Chamar, which has made her something of a lower caste icon in her native Punjab.

The lyrics that state that Chamars are more dangerous than ammunition is in effect an assertion that the days of yore when the lowest castes bore oppression meekly are gone forever.

Another song, Fan Babasaheb Di (I’m a fan of Babasaheb), is her own personal tribute to Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar, also known as Babasaheb.

Ambedkar studied under John Dewey at Harvard, obtained a degree from the London School of Economics and qualified as a Barrister in the Inns of Court in London.

He came back home to India only to discover that caste Indians could only view him through the prism of caste and were reluctant to come into any contact with him.

Disgusted, Babasaheb began a life of community mobilization urging his fellow caste men to ‘Educate, Agitate and Organise’.

Often, his strident positions on caste-related matters brought him into conflict with Mahatma Gandhi who was leading a struggle against the British.

Wanting to present a united front to the British, Gandhi attempted to co-opt Ambedkar into the struggle, something that Ambedkar resisted.

In 1933, Gandhi forced Ambedkar’s hand by going on a fast-unto-death. The contentious issue that had brought them into conflict was the issue of separate electorates for the lower castes.

To Ambedkar, separate electorates were an opportunity for his community to earn the political power that he so fervently believed would empower them. For Gandhi, it meant a break-up of his precious unity.

In later years, Ambedkar would speak bitterly of how Gandhi had railroaded him into an agreement.

Ambedkar was never a member of the Congress though he was part of the first Indian cabinet post-independence in 1947 which was largely a Congress-dominated one.

As the Law Minister, Ambedkar oversaw the writing of the Indian Constitution in which he ensured the inclusion of provisions for affirmative action for the lower castes.

Little affirmative action

While there has been a degree of success that these measures have achieved, the overall impact on society has not been that much. This is best illustrated by two instances, both of which took place this year.

In January 2016, a young Dalit student, Rohith Vemula, who was writing his doctoral thesis in the University of Hyderabad in the southern state of Telangana, took his own life.

In a poignant suicide note, he detailed the harassment he had suffered at the hands of upper-caste student politicians and faculty members on account of his political activities.

Involved with the Ambedkar Students Association, which took militant positions on caste matters, Rohith was forced to move out of the university lodgings.

For a while, he camped outside the campus in a tent hoping to draw attention to his plight before he finally decided to end his own life.

In the brouhaha that followed, among the points that activists on the one hand and ruling party members and university administrators, on the other hand, argued over was whether Rohith was actually Dalit.

Apparently, his father was not even though Rohith had largely grown up with his mother who was Dalit and as a child and young man had faced extreme prejudice and discrimination.

Among the more embarrassing revelations that tumbled out was that Rohith’s father would often beat his mother blaming her for hiding her caste origins.

The irony is that at least one of those who sat in judgment over Rohith’s political activities was the University’s vice-chancellor, Appa Rao Podile, himself accused of academic plagiarism and using political clout to hold on to his post.

Nine months after Rohith’s suicide, he is still there. Recently, Rohith’s friend and fellow Dalit, Sunkanna Vemula in a bold gesture refused to accept his doctorate from the Vice-Chancellor clearly indicating that the Rohith incident still rankled.

In another incident in a town called Una in Prime Minister’s home state of Gujarat, four young Dalit men were whipped in public in the market-place.

So brazen were the perpetrators of this crime that they actually filmed themselves committing the act and thought nothing of circulating it on social media mighty pleased with what they had done.

The supposed reason for the whipping: the four Dalit men were accused of killing a cow.

In the outrage that followed, it came to light that the four men were actually skinning a dead cow, a traditionally Dalit occupation. Nobody had thought it necessary to ask them before choosing to ‘punish’ them.

Angered, Gujarat’s Dalits mobilised in large numbers under a charismatic new leader, Jignesh Mevani, a lawyer by training.

Stating their angst at caste Hindu society’s treatment of them, Dalits undertook a march from Gujarat’s most important city, Ahmedabad to Una, a distance of 350 km.

In many places, they faced open hostility, an indication that little has changed on the issue of caste.

Different springboards

Among the more fantastic allegations that are frequently hurled at Dalits is the allegation of them being ‘freeloaders’.

Affirmative action policies (known popularly as the reservation) have ensured that a proportion of seats in higher education institutions and in government jobs are reserved for Dalits.

Dalit students sometimes find completing their courses difficult largely on account of factors having to do with their backgrounds.

Most higher education courses in India are in English, a language that the government school system where most Dalit students study, teaches only from Class 5 or 6.

Upper caste students, on the other hand have increasingly migrated to private schools that are more often than not, English-medium ones, thus placing them in a position of relative advantage.

While affirmative action policies ensure that Dalit students secure admission, there is poor support for them to actually complete their courses thereby ensuring that many Dalit students flounder for years.

The preferred upper caste term to castigate Dalits is that they lack ‘merit’. The word ‘merit’ here largely refers to the ability to pass examinations with high grades.

Upper caste students often do well in India’s cramming-oriented examination system, at least in part, due to their access to private tuitions and expensive study material that prepare them for these exams – a luxury that most Dalit students can ill-afford.

In recent years, falling agricultural yields and prices have impoverished the farming community.

Farmer castes, many of whom are only a notch or two higher than the Dalits in the caste hierarchy, have now begun clamouring for ‘reservation’ as a way out from the problems they are facing due to agricultural distress.

And the historical ill-will between landowners, many of them of subsistence-level, and labourers, traditionally Dalit, has exploded with the Dalits often ending up as victims, as in Una.

The refusal of both the current government and the previous one to tackle the issue of agricultural distress has much to do with the current clamour for reservation on the part of the farmer castes.

Defying society’s preferred order

Among the more popular notions that exist in urban India is the idea that caste is a rural phenomenon and does not exist in urban India.

Many well-heeled urban residents, mostly upper-caste, claim that it does not, though even highly-educated, wealthy people rarely transgress caste when it comes to marriage.

But many claim to be appalled at the lack of ‘merit’ implying that they themselves are highly ‘meritorious’.

This ‘no-caste’ myth is exploded from time to time as in a recent instance of the actor, Tannishtha Chatterjee writing about how she was made fun of in a TV show on account of her dark skin.

The matter of dark skin at its deepest core is linked with the issue of caste. Observers have noted that the lower castes do tend to be dark-skinned more often than not.

In India’s mythological epics, demons are almost always dark-skinned. Historians opine that those that have been portrayed as demons were probably India’s original inhabitants and it was they who were relegated to the caste boondocks when the pattern of land ownership changed.

This is a contentious issue that in the light of the fact that the evidence available is limited and largely based on conjecture has no foreseeable end.

But the fact remains that the beauty discourse in India is inextricably linked with fair skin.

Fairness creams sell in copious quantities and television advertisements often link dark skin with lack of confidence or poor perception by prospective employers in order to boost the sales of their product.

The India that exists in its cities is a society in deep denial about its many prejudices.

The middle-class upper caste establishment is convinced that the Indian dream is just as achievable as its American counterpart and caste is more often than not propped up merely as an excuse to mask one’s own incompetence.

Rural India is more honest. Its worldview is largely Darwinian.

Darwinian ideas are also linked to traditional Indian ideas about rebirth and reincarnation and one’s position in society in ‘this birth’ being linked to one’s actions in the ‘previous birth’.

Ginni Mahi through her music chooses to defy society’s preferred order. She has used her music to assert modernity’s most cherished notion—equality. That is her greatest victory.

Karthik Venkatesh is a Bangalore-based author and editor of a publishing firm. He can be reached at [email protected] . Views expressed are personal.